Semantic Scene Understanding in Robotics

An article on why semantic scene understanding could be the next big thing in autonomous robotics, where we are now, and what comes next.

I accidentally dropped my keys this morning. They fell and slid down right under the bed. I got down, making sure not to knock anything over, and tried to reach them, but they seemed out of reach. I instinctively looked around to see if I could use anything to reach the keys, and saw an unused guitar-stand nearby. It took me 4-5 seconds to dismantle the stand, and use its rod to retrieve my keys. This whole ‘side-quest’ barely cost me 25 seconds.

Being a human being, retrieving a key from under a bed is a task that is too insignificant for us to ponder over. We overcome multiple such hinderances daily, without realizing their complexity. For today’s robots (even the most advanced ones), this very task would be extremely complex. Why is that so?

Robotic arms and grippers of our age possess amazing dexterity and recent robots have overcome some of the hardest challenges in control. With advanced sensors, processors and algorithms, tasks such as localization & motion planning are more efficient than ever before. Developments in AI have made real-time object detection and tracking possible. Yet, tasks such as the one mentioned above still seem near-impossible due to a simple unanswered question: How would a robot figure out what to do in such unplanned situations?

Despite employing state-of-the-art neural networks, robots do not possess a true understanding of the semantics of their environment, i.e. the meaning of the things around them. Robots do not know how every object in their surroundings can influence their goal. Complex robot use cases (eg: disaster management and search & rescue operations) that require robots to predict possible scenarios and anticipate consequences of their actions. But they are unable to correlate knowledge from different domains with what they perceive and therefore, cannot draw logical conclusions about what can/should be done. Thus, the large gap between perception and planning is that of reasoning or common sense.

Semantic SLAM

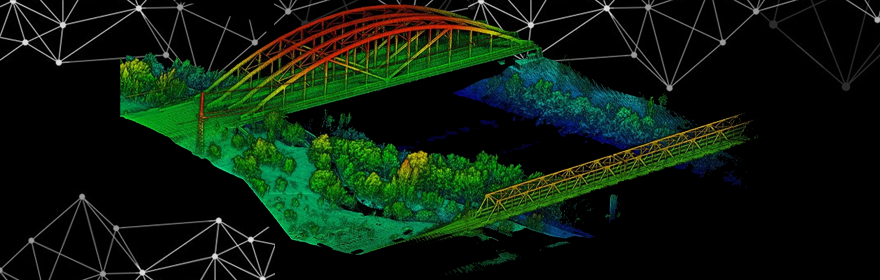

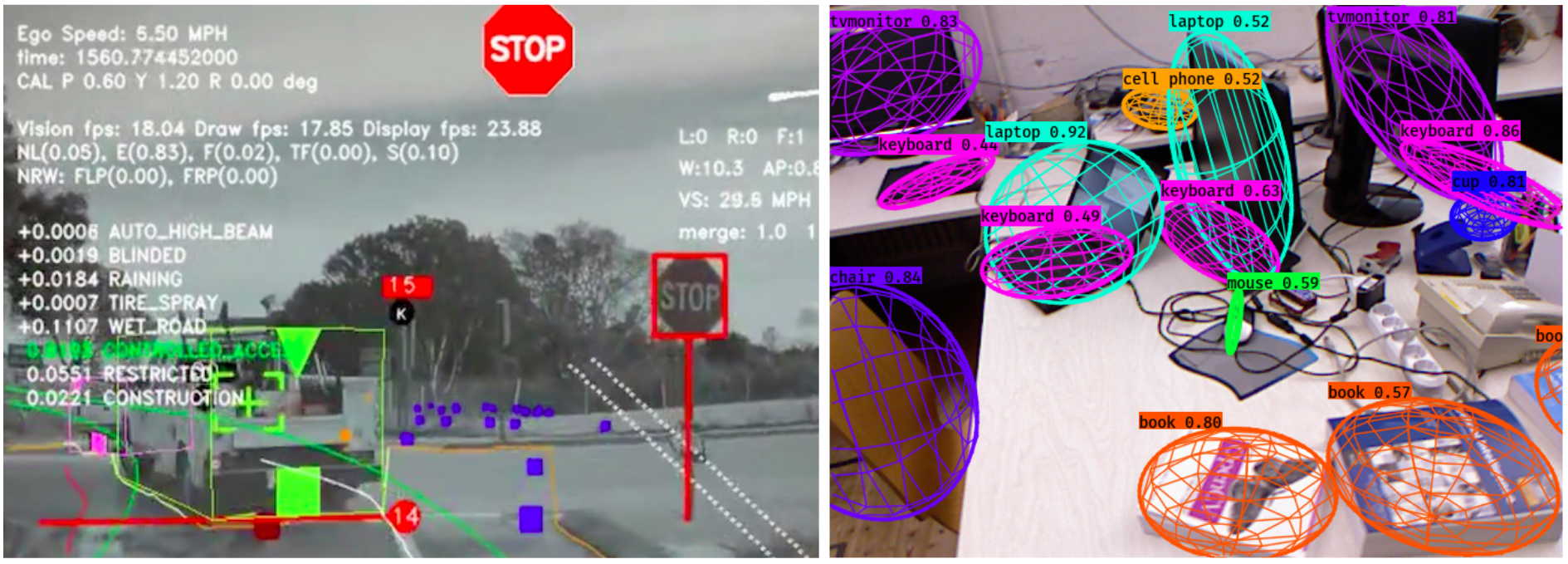

One of the relatively more explored sub-fields of semantic scene understanding is semantic SLAM (Simultaneous Localization and Mapping). Most techniques in semantic SLAM simply augment a map with semantic information. In earlier works, keypoints extracted within object detection bounding boxes are used to introduce physical constraints during SLAM. Knowledge of recognized objects can be used to introduce semantic priors (eg: A tree should be vertically oriented, the trunk should always touch the ground). Many approaches also predict 3D structures that are not fully visible, by using known shapes of common objects. This helps the robot predict occluded structures and free-spaces. Recent approaches go further by taking into account factors such as the movability, flexibility, allowed degrees of freedom and expected behaviour of known objects. Applications of these are commonly seen in self-driving cars. Here, objects like road signs, cars, signals, etc. are tracked, and known behaviours of vehicles, pedestrians, etc. are used for making predictions.

Semantic SLAM - How Tesla Autopilot sees the world (left) and augmenting SLAM with object information (right)

Inclusion of properties of individual objects in SLAM is not sufficient. For a true semantic understanding, the robot must also understand how multiple entities interact with one another. This implies that the perceived data must be further augmented with context and reasoning.

Ontology and Logic

For robots to make sense of the inter-relations of objects, our knowledge of these objects needs to be arranged in some form of conceptual hierarchy. A common approach towards this is using conceptual maps. These maps are an abstraction of the environment in terms of a graph. In some approaches, nodes represent physical area-labels (room, corridor) and their transition points (doors, gates). Other approaches further cluster objects based on which node they are associated with (eg: An oven is associated with a kitchen). Often, Machine Learning is used for this classification, i.e. associating places & objects to each other, through context. The maps are sometimes endowed with additional semantic constraints such as connectivity, movability, transition feasibility, etc.

Moving beyond simply recognizing context, robots also need to know how to use this context. An interesting way to tackle this is through the use of description sections. These are sections in the robot’s memory that would contain rules for logical inference, Bayesian predictions, heuristics, etc. There also exist algorithms that convert linear & temporal logic from these descriptive rules to controllers that can directly be used on robots.

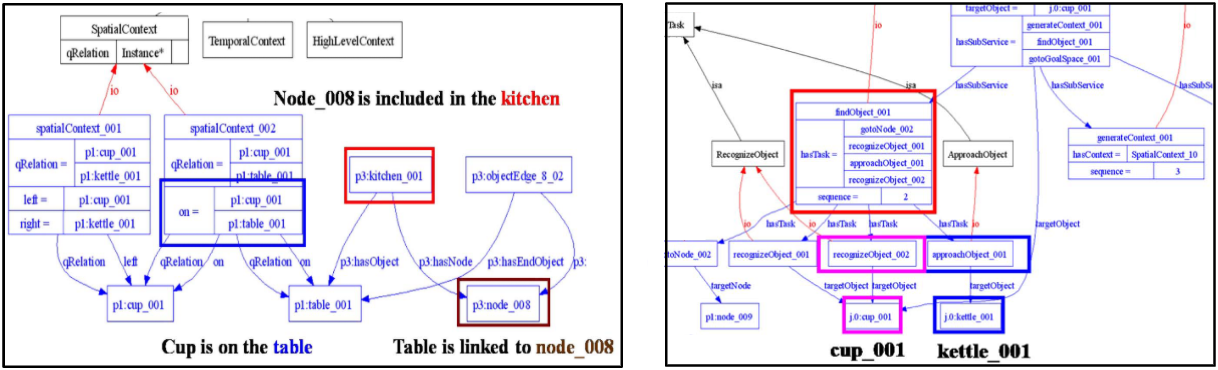

Another effective way to introduce logical reasoning in robots is by storing knowledge in an ontological structure. This is a graph that provides the robot information about what the objects are, what they can be used for and how to use them (See the figure below). Thus, by taking into account the semantics of objects, the robot can choose appropriate behaviour based on the current situation.

Ontological structures - Cropped diagram of a robot figuring out how to find a cup of tea

Learning to Reason

Hardcoding logical rules still has its limitations. Human understanding is beyond a fixed set of pre-fed rules. Humans can observe their surroundings and instantly understand what is going on through common sense. Humans can corelate past observations to gain a better understanding of the current situation.

One area where machines are getting better at gaining such an understanding is not in robotics, but in artificial video/image captioning networks. The figure below shows an AI answering questions about an image. Such architectures generally consist of a CNN-based (Convolutional Neural Network) model for object recognition giving a feature vector. This feature vector is fed to an RNN (Recurrent Neural Network) that generates a sentence describing it. It would thus be a fair assumption that at an intermediate step of this process contains a significant level of semantic understanding, embedded in latent space.

The second area of learning through observation is imitation learning. There exists research in this area that tries to solve the correspondence problem; i.e.: Humans and robots perceive and interact with the world in fundamentally different ways, so robots must learn the correspondence between the ‘state spaces’ of humans and robots. This consists of establishing Perceptual equivalence (What does an observation mean in robot-terms & human-terms) and physical equivalence (How to achieve the same effect as the one observed).

General Intelligence & Artificial Conscience

Despite all these advances, there is still a very long way to go. As we build systems with growing semantic understanding, we gradually approach towards Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). AGI can be defined as the ability of a machine to perform any task that a human can. Contemporary state-of-the-art systems are still designed to perform well on very specific tasks, but not so much on anything else. An AGI on the other hand should be able to learn a broader range of tasks with far less training. An AGI would ideally be able to apply knowledge of one domain to another.

An AGI singularity is defined as the point in the future when Artificial Intelligence surpasses human level thinking. Based on current trends of advancement in the field, some experts believe that the singularity may arrive as early as the year 2060. As each development in robotics and AI brings us closer to this point, we are moving slowly from ‘Autonomous Robots’ to 'Cognitive Robots' - robots that possess awareness, memory (episodic & procedural), ability to learn and the ability to anticipate. At such a point, AI may have the ability to figure out solutions to some of the worlds biggest and most complex challenges, and robots may be able to implement these solutions with far more ease and efficiency than humans. This would be a point when a simple task like figuring out how to retrieve keys from under a bed would truly be as insignificant for robots as it is for humans. But until then, there still remains much research to be done.

References

- R.Salas, N.Newcombe, H.Strasdat, P.Kelly, A.Davidson; SLAM++: Simultaneous localization and mapping at the level of Objects; CVPR 2013

- I.Kostavelis, A.Gasteratos; Semantic Mapping for Mobile Robot Tasks - A survey; Robotics & Autonomous Systems S66 (2015) pp86-103

- This is what a Tesla Autopilot sees on Road (Carscoop Article by S.Tudose)

- R. Zellers, Y.Bisk, A.Farhadi, Y.Choi: From Recognition to Cognition - Visual Common Sense Reasoning; CVPR 2019

- A. Pronobis, P. Jensfelt, Understanding the real world: Combining objects, appearance, geometry and topology for semantic mapping.

- G.Lim; Ontology based unified robot knoowledge for Service Robots in Indoor Environment; IEEE transactions on Systems, Man & Cybernetics Part A. Vol 41. No 3, May 2011

- C. Galindo, A. Saffiotti, S. Coradeschi, P. Buschka, J.-A. Fernandez-Madrigal, J. González: Multi-hierarchical semantic maps for mobile robotics, International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, IEEE, 2005, pp. 2278–2283

- O.M. Mozos, W. Burgard, Supervised learning of topological maps using se- mantic information extracted from range data; International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, IEEE, 2006, pp. 2772–2777

- B. Kuipers, Modeling spatial knowledge, Cogn. Sci. 2 (2) (1978) 129–153.

- Automatic Image Captioning using Deep Learning (Medium Article)

- J. Browniee, 2017 How to Automatically Generate Textual Descriptions for a Photograph with DL

- S. Wadhwa, 2018 Asking Questions to Images with Deep Learning (Floydhub Article)

- M. Tenorth, L. Kunze, D. Jain, M. Beetz, Knowrob-map-knowledge-linked semantic object maps; International Conference on Humanoid Robots, IEEE, 2010, pp. 430–435

- L.Nicholson, M.Milford, N.Sünderhauf; QuadricSLAM: Dual Quadrics from Object Detections as Landmarks in Object-oriented SLAM

- Robot Learning by Demonstration (Scholarpedia)

- How Far are we from achieving Artificial General Intelligence? (Forbes Article)

- 995 experts opinion: AGI singularity by 2060

- Cognitive Robotics (Wikipedia)